|

"The man who knows nothing of music, literature, or art is no better than a

beast," ancient Hindu wisdom warned, "only without a beast's tail or

teeth." The arts of Civilization's armor, her weapons and shield against

all the pitfalls of life, lighting the darkest corner of the trail, helping us

to cross its most dangerous passes. Indian wisdom has always extolled art as a

key to the salvation of ultimate release sought by all good Hindus. There is a

holistic quality about Indian art, a unity of many forms and artistic

experiences. Like the microcosmic universe of a Hindu temple, they help us to

climb from terrestrial trails and samsaric fears.

Art pervades every facet of

Indian life, is found on every byway of Indian Civilization. Indian art in its

purest form is Yoga, a disciplined style of worship and self-restraint that may

also be thought of as India's oldest indigenous "science." Shiva, the

" Great God" of yogic practice, visually represented as "King of

Dance" (Nataraja), is the most remarkable single symbol of divine powers

ever created by Indian artistic genius. Indian artists have celebrated and

immortalized the beauty of human bodies in bronze and stone for more than 5,000

years. We do not know the name of a single genius among the many who brought

gods to life in the Ellora, Ajanta or Elephanta, Karli caves or those who

created the Chola Natarajas as magnificent as any work by Benvenuto Cellini. The

great Rodin was possibly the most sensitive and perceptive of the admirers of

Indian art.

The

transition from cave excavation and carving to the creation of Hindu temples is

most dramatically and powerfully depicted at Ellora, where an entire mountain

has literally been scooped out over several centuries by patient devoted artists

and architectural geniuses, who envisioned and "extracted" Lord

Shiva's Mount Kailasha temple inside that enormous rock dome. Ellora's

Kailasantha cave temple remains one of the true "wonders" of the world

of art and a unique monument to Hindu devotion. Captain

Philip Meadows Taylor

(1808-1876)

author, says: "the carving

on some of the pillars, and of the lintels and architraves of the doors, is

quite beyond description. No chased work in silver or gold could possibly be

finer. Bu what tools this very hard, tough stone could have done wrought and

polished as it is, is not at all intelligible at the present day."

Indian art is so intimately

associated with Indian religion and philosophy that it is difficult to

appreciate it fully unless one has some knowledge of the ideals that governed

the Indian mind. In Indian art there is always a religious urge, a looking

beyond. From the exuberant carvings of the Hindu temples to the luminous

wall-paintings of Ajanta, to the intriguing art of cave sites and sophisticated

temple-building traditions, the Indian subcontinent offers an amazing visual

feast.

Introduction

Fine Arts - Timeline

Wonders of Elephanta

European

Reaction to Indian Art

Denigration by Marxist

historians of India

The

Master of the Dance

Aurobindo and Indian Art

Ideals

of Indian Art

Painting

Conclusion

The Plunder of Art

Introduction

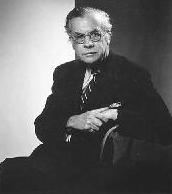

Dr.

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy

(1877-1947) scholar and art historian and late curator of Boston Museum, has observed: Dr.

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy

(1877-1947) scholar and art historian and late curator of Boston Museum, has observed:

"Indian art is essentially

religious. The conscious aim of Indian art is the intimation of Divinity. But

the Infinite and Unconditioned cannot be expressed in finite terms; and art,

unable to portray Divinity unconditioned, and unwilling to be limited by the

limitation of humanity, is in India dedicated to the representation of Gods, who

to finite man represent comprehensible aspects of an infinite whole.

Sankaracarya prayed thus: "O Lord, pardon my three sins: I have in

contemplation clothed in form Thyself that has no form; I have in praise

described Thee who dost transcend all qualities; and in visiting shrines I have

ignored Thine omnipresence."

"The

extant remains of Indian art cover a period of more than two thousand years.

During this time many schools of thought have flourished and decayed, invaders

of many races have poured into India and contributed to the infinite variety of

her intellectual resources; countless dynasties have ruled and passed away. But

just as through all Indian schools of thought there runs like

a golden thread the fundamental idealism of the Upanishads, the

Vedanta, so in all Indian art there is a unity that underlies all its

bewildering variety."

(source:

Essays on National Idealism - By Ananda K. Coomraswamy

Munshiram Manoharlal

Publishers.1981 p. 17 27-28).

From its Indo-Sumerian and Vedic-Mound beginnings

to the various peaks reached during the Maurya, Sunga, Andhra, Kusana and Gupta

periods, Indian art has been influential for centuries. The grave and sensuous

and infinitely varied arts of India have long been admired around the

world. India is vast (the size of Europe); the birthplace of great

religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism; and the home of

sophisticated civilizations dating back more than 4,000 years.

These factors

combine to give India one of the longest and most complex art traditions of the

world. Most important is the realization that "the consistent fabric of

Indian life was never rent by the Western dichotomy between religious belief and

worldly practice"--hence the easy coexistence in India of extreme religious

asceticism and the overt eroticism that pervades temples like Khajuraho and

Patan. These factors

combine to give India one of the longest and most complex art traditions of the

world. Most important is the realization that "the consistent fabric of

Indian life was never rent by the Western dichotomy between religious belief and

worldly practice"--hence the easy coexistence in India of extreme religious

asceticism and the overt eroticism that pervades temples like Khajuraho and

Patan.

A grand sweep, from the ancient cities of the Indus valley, the

development of Buddhist art (which by the 12th century had faded away in the

land of its birth), the glorious paintings of Ajanta.

In India, anonymity of artists has not been accidental; it is

a distinctive national trait.

“The modern world, with its glorification of the

personality of authors,” observes Ananda K.

Coomaraswamy, “produces work of genius and works of mediocrity,

following the peculiarities of individual artists.

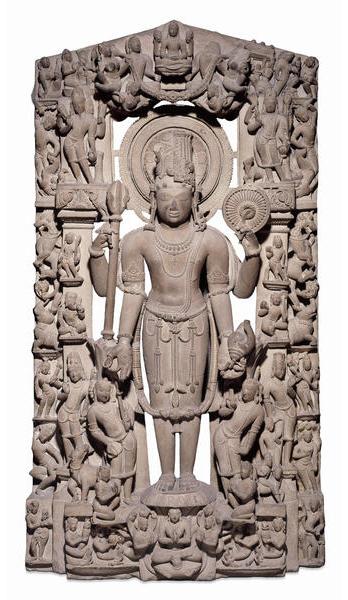

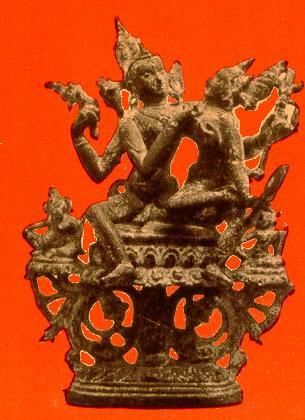

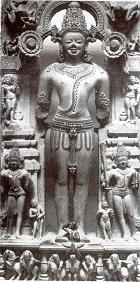

(image

source: Varuna- The

Sacred Thread - By J L Brockington p. 9).

In India, the virtue or

defect of any work is the virtue or defect of the race in that age. The names

and peculiarities of individual artists, even if we could recover them, would

not enlighten us: nothing depends upon (individual) genius or requires the

knowledge of an individual psychology for its interpretation. To understand it

at all, we must understand experience common to all men of the time and place in

which a given work was produced.”

This is true of the Vedas, as well as the marvelous Kailas

excavations; equally true of Mohenjadaro, about five thousand years ago. This

monumental anonymity is indeed writ large on the brow of our civilization.

(source: Our

Heritage and Its Significance - By Shripad Rama Sharma p.

121-122).

Sachinder Kumar Maity

(?) an author writes:

"Like India herself Indian Art is of great

antiquity and one cannot but marvel at the height reached by Indian artists

during the Classical Age."

"Indian art has contributed a unique chapter in

the history of human civilization", says E.

B. Havell. Its continued

vitality, its astonishing range - specially in the field of painting, sculpture,

and architecture, no less than the lasting sense of beauty and power it conveys,

has placed the artistic heritage among the major cultural legacies of the world.

The architecture that created the temples of Madurai, Tanjore, Khajuraho, Orissa,

the rock-cut pagodas of Mahabalipuram, the sculpture that executed the Mathura

image of Buddha, Trimurti of Elephanta, the famous Nataraja of Tanjore and the

paintings which had its efflorescence in the haunting world of beauty in the

caves of Ajanta and Ellora, and thousand others, have nothing to lose by

comparison with the whole artistic wealth of Europe during its entire

history.

(source:

Cultural

Heritage of Ancient India - By Sachindra Kumar Maity p.10-27).

Pitirim

Sorokin (1889-1968) Russian-American

sociologist of Harvard University has written:

"Art

for a Hindu is life as it is interpreted by religion and philosophy. Art for

art's sake is consequently unknown. Instead a symbolism was created to express

various qualities of the superhuman soul and superhuman figures."

(source:

Glimpses

of Indian Culture - By Dr. Giriraj Shah p. 108).

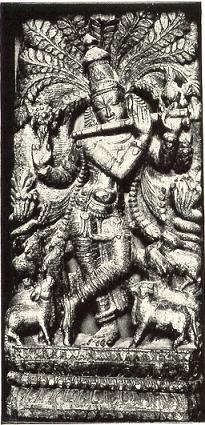

Shiva

Vishnu - destructive and creative forces of God embodied in one

being.

"Indian Art is a blossom of the tree of the Divine wisdom, full of

suggestions from worlds invisible, striving to express the ineffable."

***

Annie Wood Besant

(1847-1933) was an active socialist on

the executive committee of the Fabian Society

along with George Bernard Shaw. George Bernard Shaw regarded her the

"greatest woman public speaker of her time." Was a prominent leader of

India's freedom movement, member of the Indian National Congress, and of the

Theosophical Society. She has

said,

"Indian Art is a blossom of the tree of the Divine wisdom, full of

suggestions from worlds invisible, striving to express the ineffable, and it can

never be understood merely by the emotional and the intellectual; only in the

light of the Spirit can its inner significance be glimpsed."

(source: India's Culture

Through the Ages - By Mohan Lal Vidyarthi p. 114).

Bishop Heber (1783- 1826)

was a Church of England bishop, now remembered chiefly as a hymn-writer.

He observed that

Bishop Heber (1783- 1826)

was a Church of England bishop, now remembered chiefly as a hymn-writer.

He observed that

"the

Hindus “build like Titans, and finish like

jewelers.”

(source:

India:

Land

of the Black Pagoda - By

Lowell

Thomas

p. 326 – 329

).

Will Durant

(1885-1981) American historian has written glowingly about Hindu art:

"Before Indian art,

as before every phase of Indian civilization, we stand in humble wonder at its

age and its continuity. From the time of Mohenjodaro to the present,

through the vicissitudes of five thousand years, India has been creating its

peculiar type of beauty in a hundred arts. The record is broken and incomplete,

not because India ever rested, but because war and the idol-smashing ecstasies

of Moslems destroyed uncounted masterpieces of building and statuary, and

poverty neglected the preservation of others. Probably no other nation known to

us has ever had so exuberant a variety of arts."

"We shall never be able to do justice to

Indian art, for ignorance and fanaticism have destroyed its greatest

achievements, and have half ruined the rest. At Elephanta the Portuguese

certified their piety by smashing statuary and bas-reliefs in unrestrained

barbarity; and almost everywhere in the north the Moslems brought to ground

those triumphs of Indian architecture, of the 5th and 6th centuries, which

tradition ranks as far superior to the later works that arouse our wonder and

admiration today. The Moslems decapitated statues, and tore them limb from limb;

they appropriated for their mosques, and in great measure imitated, the graceful

pillars of the Jain temples." Time and fanaticism joined in the

destruction, for the orthodox Hindus abandoned and neglected temples that had

been profaned by the touch of alien hands." "We shall never be able to do justice to

Indian art, for ignorance and fanaticism have destroyed its greatest

achievements, and have half ruined the rest. At Elephanta the Portuguese

certified their piety by smashing statuary and bas-reliefs in unrestrained

barbarity; and almost everywhere in the north the Moslems brought to ground

those triumphs of Indian architecture, of the 5th and 6th centuries, which

tradition ranks as far superior to the later works that arouse our wonder and

admiration today. The Moslems decapitated statues, and tore them limb from limb;

they appropriated for their mosques, and in great measure imitated, the graceful

pillars of the Jain temples." Time and fanaticism joined in the

destruction, for the orthodox Hindus abandoned and neglected temples that had

been profaned by the touch of alien hands."

"We may guess at the lost grandeur of north

Indian architecture by the powerful edifices that still survive in the south,

where Moslem rule entered only in minor degree, and after some habituation to

India had softened Mohammedan hatred of Hindu ways. Col. Ferguson had counted

some thirty southern temples any one of which, in his estimate, must have cost

as much as an English cathedral." Only a Hindu

pietist rich in words could describe the lovely symmetry of the shrine at Ittagi,

in Hydrebad, or the temple at Somnathpur in Mysore, in which gigantic masses of

stone are carved with the delicacy of lace; or the Hoyshaleshwara

Temple at Halebid...Here, Ferguson adds, "the artistic combination of

horizontal and vertical lines, and the play of outline and of light and shade,

far surpass anything in Gothic art. The effects are just what the medieval

architects were often aiming at, but which they never attained so perfectly as

was done at Halebid."

If we marvel at the laborious piety that could

carve eighteen hundred feet of frieze in the Halebid temple, and could portray

in them two thousand elephants each different from all the rest, what shall we

say of the patience and courage that could undertake to cut a complete temple

out of the solid rock? But this was a common achievement of the Hindu artisans.

At Mamallapuram, on the east coast near Chennai, they carved several

rathas or pagodas, of which the fairest is the Dharma-raja-ratha, or monastery

for the highest discipline. At Ellora, a place of religious pilgrimage..

excavating out of the mountain rock great monolithic temples of

which the supreme example is the Hindu shrine of Kailasha - named after Shiva's

mythological paradise in the Himalayas. Here the tireless builder cut a hundred

feet down into the stone to isolate the block - 250 by 160 feet - that was to be

the temple; then they carved the walls into powerful pillars, statues and

bas-reliefs; then they chiseled out of the interior, and lavished there the most

amazing art: let the bold fresco of "The Lovers" serve as a specimen.

Finally, their architectural passion still unspent, they carved a series of

chapels and monasteries deep into the rock of three sides of the quarry.

(source: Story

of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage - By Will Durant

MJF Books.1935 p. 584-585).

Richard Lannoy

(1928 - ) author of

several books including, The

Speaking Tree: A Study of Indian Culture and Society

has pointed out that the caves of India are the most singular fact about

Indian art, and he is right, for they serve to distinguish it from that of other

civilizations. A prodigious amount or labor, spread over a period of about 1,300

years, was expended in this “art of mass”, the excavations of rock

sanctuaries and monasteries. These caves were hewn out of solid rock; in other

words, they were “constructed” through the excavation of space. These

sanctuaries were cut from nearly-perpendicular cliffs to a depth of a hundred

feet: in all cases, this excavation was carried out by means of a chisel ¾

inches wide; the same chisel was also used to carve out elaborately decorated

columns, galleries, and shrines. The two largest

structures of the kind are staggering in their dimensions.

(source:

Decolonizing

History: Technology and Culture in India, China and the West

1492 to the Present Day - By Claude Alvares p.72-73).

Alain Danielou

a.k.a

Shiv Sharan (1907-1994), son of French

aristocracy, author of numerous books on philosophy, religion, history and arts

of India.

He was perhaps the first European to boldly

proclaim his Hinduness. He had a wide effect upon Europe's understanding of

Hinduism. He explained: Alain Danielou

a.k.a

Shiv Sharan (1907-1994), son of French

aristocracy, author of numerous books on philosophy, religion, history and arts

of India.

He was perhaps the first European to boldly

proclaim his Hinduness. He had a wide effect upon Europe's understanding of

Hinduism. He explained:

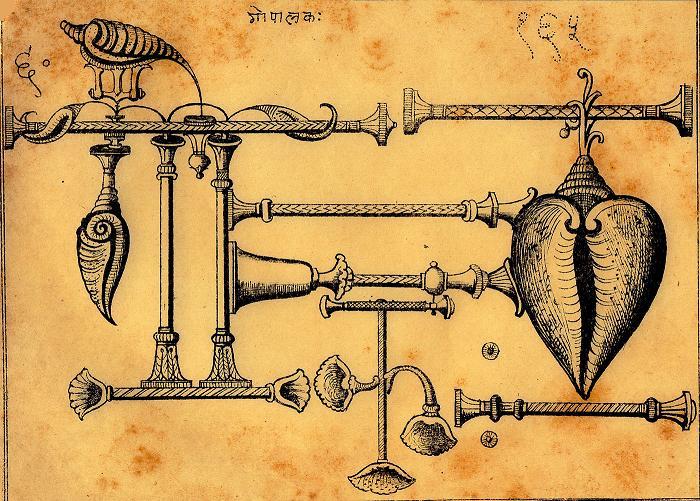

"The

artist must prepare a geometrical design in accordance with the symbolic

proportions required for the image he wants to represent. He must concentrate

his vision and his thought on the magic diagram or yantras, till he perceives

through the geometrical outlines the form he is to sculpture. This concentration

of the artist is one of the highest and completest form of concentration."

(source:

Glimpses

of Indian Culture - By Dr. Giriraj Shah p. 108).

Dr.

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy

(1877-1947) Indian art historian, a remarkable critic, scholar and mystic, late

curator at the Boston Museum, who dazzled the Western world with his

message concerning the spiritual greatness of Indian art. A pioneer

historian of Indian art and foremost interpreter of Indian culture to the West. He

detected in India “a strong national genius... since the beginning of her

history.” He found Indian art and culture “a joint creation

of the Dravidian and Aryan genius.” Of Buddhism, he wrote:’ “the more

profound our study, the more difficult it becomes to distinguish Buddhism from

Brahmanism, or to say in what respects, if any, Buddhism is really unorthodox.

The outstanding distinction lies in the fact that Buddhist doctrine is

propounded by an apparently historical founder. Beyond this there are only broad

distinctions of emphasis.”

Indian art had accompanied Indian religion across

straits and frontiers into Sri Lanka, Java, Cambodia, Siam, Burma, Tibet, Khotan,

Turkestan, Mongolia, China, Korea, and Japan; "in Asia all roads lead to

India." Angkor Vat a masterpiece equal to the finest architectural

achievements of the Egyptians, the Greeks, or the cathedrals of Europe. An

enormous moat, twelve miles in length, surrounds the temple; over the moat runs

a paved bridge guarded by dissuasive Nagas in stone; then an ornate enclosing

wall; then spacious galleries, whose relief's tell again the tales of the Mahabharata

and Ramayana; then the stately edifice

itself, rising upon a broad base, by level after level of a terraced pyramid, to

the sanctuary of the god, two hundred feet high. Indian art had accompanied Indian religion across

straits and frontiers into Sri Lanka, Java, Cambodia, Siam, Burma, Tibet, Khotan,

Turkestan, Mongolia, China, Korea, and Japan; "in Asia all roads lead to

India." Angkor Vat a masterpiece equal to the finest architectural

achievements of the Egyptians, the Greeks, or the cathedrals of Europe. An

enormous moat, twelve miles in length, surrounds the temple; over the moat runs

a paved bridge guarded by dissuasive Nagas in stone; then an ornate enclosing

wall; then spacious galleries, whose relief's tell again the tales of the Mahabharata

and Ramayana; then the stately edifice

itself, rising upon a broad base, by level after level of a terraced pyramid, to

the sanctuary of the god, two hundred feet high.

Here magnitude does not detract

from beauty, but helps it to an imposing magnificence

that startles the Western mind into some weak realization of the ancient

grandeur once possessed by Oriental civilization.

(source: Story

of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage By Will Durant

MJF Books.1935 p.601).

"The Hindus do not regard the religious,

aesthetic, and scientific standpoints as necessarily conflicting, and in all

their finest work, whether musical, literary, or plastic, these points of view,

nowadays so sharply distinguished, are inseparably united.

(source: The

Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon - By Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

p. 17).

"All that India can offer proceeds from her

philosophy, a state of mental concentration (yoga) on the part of the artist and

the enactment of a certain amount of ritual being postulated as the source of

the 'spirituality' of Indian art."

(source: The

Dance of Siva: Fourteen Indian Essays - By Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

p. 21).

In the process of comparing both the European and

Oriental traditional philosophy of art, a task, it would seem, which had

convinced him of the perennial value of the traditional point of view since the

works of art as in the case of the Indian sub-continent and its environs

appeared to him to endure and increase in value down

through the ages.

Rizwan Salim (

? ) reviewer,

and assistant editor, American Sentinel,

has written eloquently about Hindu art:

"It is clear that India

at the time when Muslim invaders turned towards it (8 to 11th century) was the

earth's richest region for its wealth in precious and semi-precious stones, gold

and silver; religion and culture; and its fine arts and letters. Tenth century

Hindustan was also too far advanced than its contemporaries in the East and the

West for its achievements in the realms of speculative philosophy and scientific

theorizing, mathematics and knowledge of nature's workings. Hindus of the early

medieval period were unquestionably superior in more things than the Chinese,

the Persians (including the Sassanians), the Romans and the Byzantines of the

immediate preceding centuries. The followers of Siva and Vishnu on this

subcontinent had created for themselves a society more mentally evolved - joyous

and prosperous too - than had been realized by the Jews, Christians, and Muslim

monotheists of the time. Medieval India, until the Islamic invaders destroyed

it, was history's most richly imaginative culture and one of the five most

advanced civilizations of all times."

Ancient

Hindu temple architecture is the most awe-inspiring, ornate and spellbinding

architectural style found anywhere in the world. No artists of any historical

civilization have ever revealed the same genius as ancient Hindustan's artists

and artisans.

(source: Need

for Cultural pride - Revival - By Rizwan Salim The Hindustan

Times 9/20/1998).

Dr.

Ernest Binfield Havell (1861-1934)

principal to the Madras College of

Art in the 1890s and left as principal of the Calcutta College of Art some 20

years later. His major ideas about Indian art theory are to be found in his two works, Indian

Sculpture and Painting (1908) and, more important, The Ideals of Indian Art

(1911). The Ideals of Indian Art was written with the express purpose of

changing the prevailing European indifference to Indian art and bringing about a

proper appreciation of its aesthetic qualities. Dr.

Ernest Binfield Havell (1861-1934)

principal to the Madras College of

Art in the 1890s and left as principal of the Calcutta College of Art some 20

years later. His major ideas about Indian art theory are to be found in his two works, Indian

Sculpture and Painting (1908) and, more important, The Ideals of Indian Art

(1911). The Ideals of Indian Art was written with the express purpose of

changing the prevailing European indifference to Indian art and bringing about a

proper appreciation of its aesthetic qualities.

"Indian artistic expression begins from a

starting-point far removed from that of the European. Only an infinitesimal

number of Europeans, even of those who pass the best part of their lives in

India, make any attempt to understand the philosophic, religious, mythological

and historical ideas of which Indian art is the embodiment."

In other words, he was perceptive enough to see

that it was vital to judge work of Indian art on the basis of standards of art

criticism evolved within the Indian tradition instead of employing European

standards which were extraneous to the tradition.

(source: Much Maligned

Monsters: A History of European Reactions to Indian Art - By Partha Mitter

p. 271).

"'The opposition of Western materialism to the

philosophy of the East always makes it difficult for the Europeans to approach

Indian art with anything like unprejudiced minds. The whole of modern European

academic art-teaching has been based upon the unphilosophical theory that beauty

is a quality which is inherent in certain aspects of matter or form.."

Indian thought takes a much wider, a more

profound and comprehensive view of art. The Indian artist has the whole creation

and every aspect of it for his field; not merely a limited section of it, mapped

out by academic professors. Beauty, says the Indian philosopher, is subjective,

not objective. It is not inherent in form or matter; it

belongs only to spirit, and can only be apprehended by spiritual vision. "

(source: The

Art Heritage of India - By Ernest Binfield Havell p. 134-135).

He also

pointed out the fallacy and absurdities of some Western historians to find some

foreign influence on Indian art. He said:

"Indian

art was inspired by Indian Nature, Indian philosophy and religious teaching, and

no one."

(source:

Glimpses

of Indian Culture - By Dr. Giriraj Shah p. 115).

Havell thought Indian art was conceptual, aiming

at the realization of 'something finer and subtle than ordinary physical beauty.

The image that the Indian created came from inside his head; he had no need of a

goose-pimpled model posing uncomfortably in his studio. His achievement was not

that of capturing real life in art, but of giving birth to an abstract

ideal. He said: " A figure with three heads, and four, six or eight

arms, seems to a European a barbaric conception, though it is not less

physiologically impossible than the wings growing from the human scapula in the

European representation of angels.... But it is altogether foolish to condemn

such artistic allegories a priori because they do not conform to the canons of

the classic art of Europe. All art is suggestion and convention, and if Indian

artists can suggest divine attributes to Indian people with Indian culture, they

have fulfilled the purpose of their art." Havell thought Indian art was conceptual, aiming

at the realization of 'something finer and subtle than ordinary physical beauty.

The image that the Indian created came from inside his head; he had no need of a

goose-pimpled model posing uncomfortably in his studio. His achievement was not

that of capturing real life in art, but of giving birth to an abstract

ideal. He said: " A figure with three heads, and four, six or eight

arms, seems to a European a barbaric conception, though it is not less

physiologically impossible than the wings growing from the human scapula in the

European representation of angels.... But it is altogether foolish to condemn

such artistic allegories a priori because they do not conform to the canons of

the classic art of Europe. All art is suggestion and convention, and if Indian

artists can suggest divine attributes to Indian people with Indian culture, they

have fulfilled the purpose of their art."

Just as angels are given wings, or saints halos,

or just as the Holy Spirit was portrayed as a dove, so Shiva or Vishnu were

given extra arms to hold the symbols of their various attributes, or extra heads

for their different roles. Havell showed how consummately the Indian artist

could handle movement. Taking the example of the famous Nataraja (dancing Shiva)

bronzes of south India, he first explored its symbolism. No work of Indian art

is without a wealth of allegory and symbol, ignorance of which was, and still

is, a major stumbling block for most non-Indians. The Nataraja deals with the

divine ecstasy of creation expressed in dance.

(image

source: India Ceylon Bhutan Nepal and the Maldives - By

The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples - volume 2. p.

265).

"Art will

always be caviare to the vulgar,

but those who would really learn and understand it should begin with Indian art,

for true Indian art is pure art, stripped of the superfluities and vulgarities

which delight the uneducated eye. Yet Indian art, being more subtle and

recondite than the classical art of Europe, requires a higher degree of artistic

understanding, and it rarely appeals to European dilettanti, who with a

smattering of perspective, anatomy, and rules of proportion added to their

classical scholarship, aspire to be art critics, amateur painters, sculptors or

architects, and these unfortunately have the principal voice in art

administration in Indian."

Comparing the European and Hindu art, Havell

says:

"European art has, as it were its wings

clipped: it knows only the beauty of earthly things. Indian art, soaring into

the highest empyrean, is ever trying to bring down to earth something of the

beauty of the things above."

(source: Indian

Sculpture and Painting - By

Ernest Binfield Havell Elibron

Classics reprint. Paperback. New. Based on 1908 edition by John Murray, London.

p. 24

- 69).

Dr. James Fergusson architectural

historian, has made the following observation regarding Hindu art:

"When Hindu sculpture first dawns upon us in

the rails of Buddha Gaya and Bharhut, 220 to 250 B.C. it is thoroughly original,

absolutely without, a trace of foreign influence, but quite capable of

expressing in ideas, and of telling its story with a distinctness that never was

surpassed, at least in India....For an honest, purpose-like, pre-Raphaelite kind

of art, there is probably nothing much better to be found anywhere."

(source: Indian

and Eastern Architecture - By James

Fergusson).

Baron John Emerich

Edward Dalberg Acton (1834 -1902) English historian, was greatly struck

with the architecture of Dwaraka, which he calls 'the wonderful city," and

says:

"The natives of that country (India) have carried the art of

construction and ornamenting excavated grottoes to a much higher degree of

perfection than any other people."

(source: Geographical

Ephemerides, Volume XXXII, p. 12).

According to Rene

Grousset (1885-1952) French art Historian. Author of several

books including Civilization of India and

The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. According to Rene

Grousset (1885-1952) French art Historian. Author of several

books including Civilization of India and

The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia.

He writes about the Indian

influence in South East Asia:

"In

the high plateau of eastern Iran, in the oases of Serindia, in the arid wastes

of Tibet, Mongolia, and Manchuria, in the ancient civilized lands of China and

Japan, in the lands of the primitive Mons and Khmers and other tribes of

Indo-China, in the countries of the Malaya-Polynesians, in Indonesia and Malay, India

left the indelible impress of her high culture, not only upon religion, but also

upon art, and literature, in a word, all the higher things of spirit."

Angkor wat, Cambodia.

India

left the indelible impress of her high culture, not only upon religion, but also

upon art, and literature, in a word, all the higher things of spirit."

For

more on Greater India refer to chapter on Suvarnabhumi

and Sacred Angkor.

***

"There is an obstinate

prejudice thanks to which India is constantly represented as having lived, as it

were, hermetically sealed up in its age-old civilization, apart from the rest of

Asia. Nothing could be more exaggerated. During the first eight centuries of our

era, so far as religion and art are concerned, central Asia was a sort of Indian

colony. It is often forgotten that in the early Middle

Ages there existed a "Greater

India," a vast Indian empire. A

man coming from the Ganga or the Deccan to Southeast Asia felt as much at home

there as in his own native land. In those days the Indian Ocean really deserved

its name."

(source: Civilizations

of the East - By Rene Grousset

Vol. II, Chapter - Farther India and the Malay Archipelago p. 275-343). For

more on Greater India refer to chapter on Suvarnabhumi

and Sacred Angkor.

He

gives a fine interpretation of the image of Nataraja:

“Whether

he be surrounded or not by the flaming aureole of the Tiruvasi (Pabhamandala)

– the circle of the world which he both fills and oversteps – the King of

the Dance is all rhythm and exaltation. The tambourine which he sounds with one

of his right hands draws all creatures into this rhythmic motion and they dance

in his company. The conventionalized locks of flying hair and the blown scarfs

tell of the speed of this universal movement, which crystallizes matter and

reduces it to powder in turn. One of his left hands holds the fire which

animates and devours the worlds in this cosmic whirl. One of the God’s feet is

crushing a Titan, for “this dance is danced upon the bodies of the dead”,

yet one of the right hands is making a gesture of reassurance (abhayamudra), so

true it is that, seen from the cosmic point of view…the very cruelty of this

universal determinism is kindly, as the generative principle of the future. And,

indeed, on more than one of our bronzes the King of the Dance wears a broad

smile. He smiles at death and at life, at pain and at joy, alike, or

rather,..his smile is death and life, both joy and pain…'

Lord Shiva:

the King of

the Dance is all rhythm and exaltation.

‘‘the dancing

Shiva is the dancing universe, the ceaseless flow of energy going

through an infinite variety of patterns that melt into one

another’’.

Lord

Shiva Nataraja — shows that

the ancient seers’ revelations encompass concepts which are at once

both mystical and tantalizingly scientific.

***

From

this lofty point of view, in fact, all things fall into their place, finding

their explanation and logical compulsion. Here art is the faithful interpreter

of a philosophical concept. The plastic beauty of the rhythm is no

more than the expression of an ideal rhythm. The very multiplicity of arms,

puzzling as it may seem at first sight, is subject in turn to an inward law,

each pair remaining a model of elegance in itself, so that the whole being of

the Nataraja thrills with a magnificent harmony in his terrible joy. And as

though to stress the point that the dance of the divine actor is indeed a sport,

(lila) – the sport of life and death, the sport of creation and destruction,

at once infinite and purposeless – the first of the left hands hangs limply

from the arm in the careless gesture of the gajahasta (hand as the elephant’s

trunk). And lastly, as we look at the back view of the statue, are not the

steadiness of these shoulders which uphold world, and the majesty of this

Jove-like torso, as it were a symbol of the stability and immutability of

substance, while the gyration of the legs in its dizzy speed would seem to

symbolize the vortex of phenomena.”

(source:

The Civilization of the East – India - by Rene

Grousset p. 252 - 53).

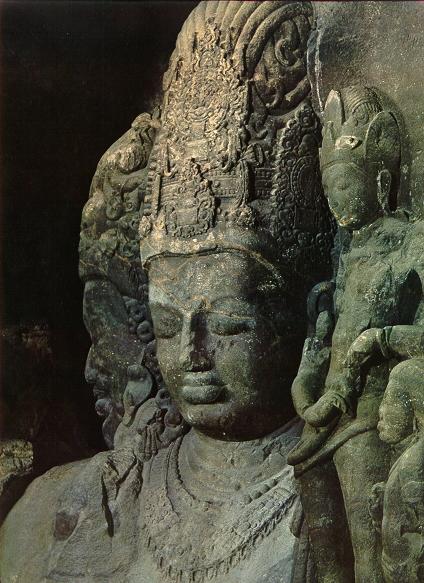

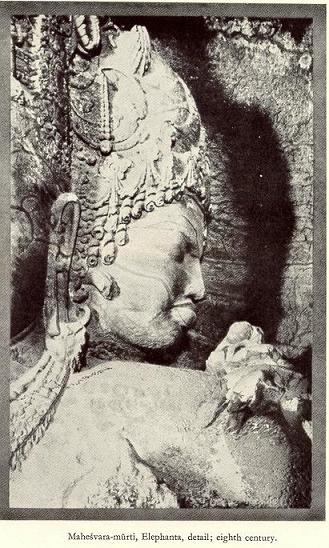

He speaks of the Trimurti

statue at Elephanta Caves:

"Universal

art has succeeded in few materialization of the Divine as powerful and also as

balanced. He believed that it is "the greatest representation of

the pantheistic god created by the hands of man."

He concludes with poetic

enthusiasm: "Never have the overflowing sap of life, the pride of force

superior to everything, the secret intoxication of the inner god of things been

so serenely expressed."

(source: The

India I Love - By Marie-Simone Renou p. 88-93).

In the words of Rene Grousset,

" The three countenances of the one being are here harmonized without a

trace of effort. There are few material representations of the divine principle

at once as powerful and as well balanced as this in the art of the whole world.

Nay, more, here we have undoubtedly the grandest representation of the

pantheistic God ever made by the hand of man...Indeed, never have the exuberant

vigor of life, the tumult of universal joy expressing itself in ordered harmony,

the pride of a power superior to any other, and the secret exaltation of the

divinity immanent in all things found such serenely expressed."

(source: The

Civilization of the East – India - by Rene Grousset p.245-6).

In its Olympian majesty, the

Mahesamurti of Elephanta is worthy of comparison with the Zeus of Mylasa or the

Asklepios of Melos."

(source: Civilizations

of the East - By Rene Grousset

Vol. II, p. 245-246).

"The principal relief at Mallalipuram is the

great rock-carving known as the Gangacatarna "descent of the Ganga".

This enormous sculpture is high relief, measuring nearly 30 yards in length and

23 feet in height and entirely covering one face of the cliff, groups a whole

world of animals, ascetics, genii, and gods round the cascade in which sports a

band of nagas and nagis, symbolic of the sacred waters. What we have before us

here is a vast picture, a regular fresco in stone.

This relief is a masterpiece

of classic art in the breadth of its composition, the sincerity of the impulse

which draws all creatures together round the beneficent waters, and its deep,

fresh love of nature. In particular we may draw attention to the ascetic

prostrating himself on the left of the cascade; this amazingly realistic figure

with its synthetic, rugged, and direct workmanship, at once restless and simple,

has all the quality of a Rodin."

(source: Civilizations

of the East - By Rene Grousset

Vol. II, Chapter -

Farther India and the Malay Archipelago

p. 230).

Abu

Fasl (1551 - 1602) was the vizier of the great Mughal emperor Akbar

and author of the Akbarnama the official history of Akbar's reign

.

He wrote of this singular

architecture of Konark thus:

“Its

cost was defrayed by twelve years’ revenue of the province. Even those whose

judgment is critical, and who are difficult to please, stand astonished at its

sight.”

(source:

India:

Land

of the Black Pagoda - By

Lowell

Thomas

p. 326 – 329

).

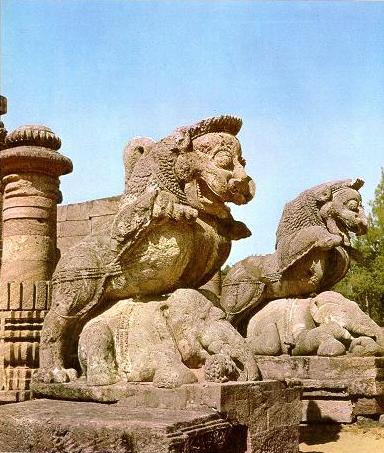

The Konark war-horse,

prancing into battle with a massively strong warrior striding beside it.

***

Of the colossal war-horse placed outside the

Southern facade of the black Pagoda at Kanarak in Orissa, built about the middle

of the thirteenth century by Narsingaha I, art critic E.

B. Havell says:

"Here Indian sculptors

have shown that they can express with as much fire and passion as the greatest

European art the pride of victory and the glory of triumphant warfare, for not

even the Homeric grandeur of the Elgin marbles surpasses the magnificent

movement and modelling of this Indian Achilles, and the superbly monumental

war-horse in its massive strength and vigor is not unworthy of comparison with

Verocchio's famous masterpieces at Venice!"

(source: Indian

Sculpture and Painting - By

Ernest Binfield Havell Elibron

Classics reprint. Paperback. New. Based on 1908 edition by John Murray, London.

p. 147)

The Konark war-horse,

prancing into battle with a massively strong warrior striding beside it,

appealed to Havell because it also showed that the Indian sculptor was quite

capable of handling martial themes. "Not even the Homeric grandeur of the

Elgin marbles surpasses the magnificent movement and modeling of this Indian

Achilles, and the superbly monumental war-horse with its massive strength and

vigor is not unworthy of comparison with Verocchio's famous masterpiece at

Venice."

(source: India

Discovered - By John Keay

p. 106-107).

V. S. Naipaul (1932 - ) Nobel Laureate, was born in Trinidad into a

family of Hindu origin is known for his penetrating

analyses of alienation and exile. He has discussed

some of his controversial ideas about rewriting Indian history:

"I am less interested in the Taj

Mahal which is a vulgar, crude building, a display of power

built on blood and bones. Everything

exaggerated, everything overdone, which suggests a complete

slave population. I would like to find

out what was there before the Taj Mahal."

(source: How

do you ignore history?' - interview -

economictimes.indiatimes.com - January 13' '03).

As J

D Beglar, the assistant-director of the Archaeological Survey of

India (ASI), in his Report for 1871-72, wrote: "It is only after the Mughal

conquest of India that Muhammadan architecture begins to be beautiful".

Before that the Islamic approach to architecture was barbarous. According to the

reading of the invaders, "their religion demanded the suppression of

aesthetic feelings".

Hindu art has been

incomprehensible to most Western critics, particularly of the colonial era and

they often used harsh epithets like 'barbarous', 'ugly', etc. to describe it.

But it was not so with Huxley. He found much in Indian art to appreciate even

while he used Western standards of judgment.

Aldous Huxley

(1894-1963) the English novelist and

essayist, born into a family that included some of the most distinguished members of the

English ruling class, found: Aldous Huxley

(1894-1963) the English novelist and

essayist, born into a family that included some of the most distinguished members of the

English ruling class, found:

"The Hindu architects produced buildings incomparably more rich and

interesting as works of art. I have not visited Southern India, where, it is

said, the finest specimen of Hindu architecture are to be found. But I have seen

enough of the art in Rajputana to convince me of its enormous superiority to any

work of the Mohammedans. The temples at Chittor, for example, are specimens of

true classicism." "Mohammedan art tends ..to be dry, empty,

barren, and monotonous. Huxley also visited the Taj at Agra and he was much

disappointed. He found the building expensive and picturesque but

architecturally uninteresting. He thought that it was elegant but its elegance

was of a "very dry and negative kind", and its classicism came not

from any "intellectual restraint imposed on an exuberant fancy", but

from "an actual deficiency of fancy, a poverty of imagination". Comparing

it with Hindu architecture, he said: "The Hindu architects produced

buildings incomparably more rich and interesting as works of art.

According to him, its fabulous "costliness is what most people seem to like

about the Taj", and that because it is made of marble. But

"marble", he says, "covers a multitude of sins." Its

costliness makes up for its lack of architectural merit.

It could be said that art is not Islam's forte as

it repudiates it and, therefore, it has not developed. It had little to convey

or communicate in the way of deeper spiritual truths. Its God was best satisfied

with demolition of the shrines of "other Gods", and it was in that

direction that Islam found its best self-expression." It shared this

passion of demolition with other iconoclastic religions including Christianity -

we forget what it did in its heyday.

(source: On

Hinduism Reviews and Reflections - By Ram Swarup

p.161-165).

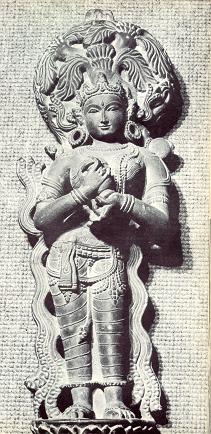

A head of Mukhilinga, an

incarnation of Lord Shiva.

(image

source: India Ceylon Bhutan Nepal and the Maldives - By

The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples - volume 2. p. 322).

Rajarajeshvara Temple, Tanjavur,

completed in 1010, dedicated to Lord Shiva, the temple is superb example of

southern Chola style.

(image source: Indian

Art - By Vidya Deheja p. 206).

For more

refer to chapter on Greater

India: Suvarnabhumi and Sacred

Angkor. For a

documentary on Hindu temples, refer to The

Lost Temples of India

***

Sir William Wilson

Hunter (1840-1900) entered the Indian civil service in 1862. He was

a man of broad cultural interests and was author of several notable volumes

mainly on Indian historical subjects, acknowledges England's debt to India:

"English decorative art in our day has

borrowed largely from Indian forms and patterns. The exquisite scrolls on the

rock temples at Karli and Ajanta, the delicate marble tracey and flat

wood-carving of Western India, the harmonious blending of forms and colors in

the fabrics of Kashmir, have contributed to the restoration of tastes in

England. Indian art-work, when faithful to native designs, still obtains the

highest honors at the international exhibitions of Europe. "

(source: The

Indian Empire - By

Sir William Wilson Hunter p. 155).

Jawaharlal Nehru

(1889-1964) first

prime minister of free India, says: "The amazing expansion of Indian culture and art to other countries

has led to some of the finest expressions of this art being found outside India.

Unfortunately many of our old monuments and sculptures, especially in northern

India, have been destroyed by invaders in course of time."

(source: The

Discovery of India -

By Jawaharlal Nehru p. 210).

Lost Temples of

India

If you switch on The History

Channel, you are overwhelmed with documentaties on Egypt. Every pyramid, every

pharoah and every single grain of sand has a documentary. “Ancient Secrets of

Egypt”, “Really Ancient Secrets of Egypt”, “The secret of the pyramids”, “The

Pharoah’s slave’s wife’s second cousin’s story”, so goes the list.

But if you ask which Indian emperor has moved more

stone than the pyramid in Giza to construct a temple, everyone would blink.

It was refreshing to see the

documentary called The

Lost Temples of India on

the Big Temple at Tanjore, constructed by Raja Raja

Chola. The documentary talks about how Raja Raja selected elephants

for battle, how he moved 40 tonne granite stones to build the temple and the

techniques used for cutting granite. They even find the remains of the ramp

which could have been used for sliding up the stones.

(source:

Lost Temples of India).

Sir Edwin Arnold

(1832-1904) poet and

scholar and Author of The

Song Celestial, which is a translation of the Bhagavad

Gita. His description of the Elephanta caves is very fine. He says of the statue of

Ardhanareswara:

"This statue of colossal size, is

nevertheless very delicately cut, and the limbs and features possess an almost

tender beauty."

In regard to Indian sculpture he writes: "Everywhere -

on plinth and abacus, frieze and entablature - appears the same lavish wealth of

work and fancy; for it is characteristic of the Hindu art, which the Moslem also

in this respect adopted, to leave no naked plans in the stone."

He speaks of the Meenakshi temple at Madura thus:

"Each gopuram looks like a mountain of bright and shifting hues, in the

endless detail of which the astonished vision becomes lost....Imagine four of

these carved and decorated pyramidal pagaodas, each equally colossal and

multi-colored with fine minor ones clustering near, anyone of which would singly

make a town remarkable!"

(source: Eminent

Orientalists: Indian European American - Asian Educational

Services. p. 251-254).

Lions resting upon elephants

guard the gateway of the Surya Deul, or Temple of the Sun in Orissa. The triumph

of the lion over the elephant is thought to represent the victory of the sun

over the rain.

(image

source: India Ceylon Bhutan Nepal and the Maldives - By

The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples - volume 2. p.

290).

***

M. Rene Grousset

(1885-1952) French art historian, says: "In the high plateau of eastern

Iran, in the oases of Serindia, in the arid wastes of Tibet, Mongolia, and

Manchuria, in the ancient civilized lands of China and Japan, in the lands of

the primitive Mons and Khmers and other tribes of Indo-China, in the countries

of the Malaya-Polynesians, in Indonesia and Malay, India

left the indelible impress of her high culture, not only upon religion, but also

upon art, and literature, in a word, all the higher things of spirit."

(source: Civilizations

of the East - By Rene Grousset

Vol. II, p. 276).

Captain Philip

Meadows Taylor

(1808-1876)

a lieutenant in the Nizam of Hyderabad's

army who learned Persian and Hindi. Author of

Confessions

of a Thug (1839)

says of the Ellora caves:

"the carving on some of the pillars, and of the lintels and architraves of

the doors, is quite beyond description. No chased work in silver or gold could

possibly be finer. Bu what tools this very hard, tough stone could have done

wrought and polished as it is, is not at all intelligible at the present

day."

(source: Story

of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage By Will Durant

MJF Books. 1935 p. 601).

Colonel James Tod,

after carefully examining and exploring the temple at Barolli (Rajasthan)

exclaims: "To describe its stupendous and diversified architecture is

impossible; it is the office of the pen alone, but the labor would be endless. Art

seems to have exhausted itself, and we are perhaps now for the first time fully

impressed with the beauty of Hindu sculpture. The columns, the

ceilings, the external roofing, where each stone presents a miniature temple,

one rising over another until the crown, by the urn-like kalasha, distract our

attention. The carving on the capital of each column would require pages of

explanation, and the whole, in spite of high antiquity, is in wonderful

preservation."

"The doorway, which is destroyed, must have

been curious, and the remains that choke up the interior are highly interesting.

One of these specimens was entire and unrivalled in taste and

beauty."

(source: Annals

& Antiquities of Rajas'than - Col. James Tod Volume II. p.

704).

Temple

gods that display a shocking beauty

To

the Western eye, these gods and goddesses are, given their sacred function,

almost shockingly beautiful. Divinity and sensuous, sexual beauty seem to be

inextricably mixed. But the appreciation of a god's physical beauty was one of

India's customary approaches to the divine. Perfection of the body was

considered a prerequisite for the flow of inner beauty and supremacy of spirit.

If

we look at the Goddess Uma, for example, she is portrayed as a slender,

seductive and exquisitely beautiful woman. She has a statuesque and graceful

figure, her full breasts are softly sculpted and her skirt is slung so low as to

reveal the curve of her stomach. Other deities, too, such as the superb Shiva,

Lord of Dance, are exquisitely elegant with their perfectly proportioned thighs

and legs, plump and supple and decorated with folds of tightly drawn cloth, and

their long curved feet and fingers.

Goddess

Uma: There is grace in elegance

To

the Western eye, these gods and goddesses are, given their sacred function,

almost shockingly beautiful.

***

These

figures are nearly 1,200 years old, yet their details are still remarkably

crisply defined. The lost wax method of modelling was done to such high

standards, both technically and aesthetically, that it is still used today

unchanged.

No

wonder François-Auguste-René

Rodin (1840-1917), one of our masters of bronze

modelling, whose work can be seen at the Royal Academy, was

overwhelmed when he saw the Chola

sculpture in 1913.

"There are

things that other people do not see: unknown depths, the wellsprings of

life," he said.

"There is grace in

elegance; above grace, there is modelling; everything is exaggerated; we call it

soft but it is most powerfully soft! Words fail me then."

(source:

Chola:

Sacred Bronzes of Southern India - By

Joanna Pitman at the Royal Academy

- The Times).

Top of Page

Fine Arts - Timeline

1. Sindhu-Saraswati Valley Culture

The highest expression of Indian proto historic

culture was the Sindhu Saraswati Valley culture, after its main center. In spite

of a sense of practicality, the figures displayed on the many seals executed in

stone, steatite, ceramics and metal display an advanced aesthetic quality. The

copper figure of a dancer and the torsos of figures, are not treated with the

rigid and coarse style typical of ancient art, but with a

delicate sensitivity of feeling for the graceful movements of the dance and the

clear concept of free representation of the human figure.

2. The Mauryan Dynasty

The Mauryans left traces of their rule in the

great royal palaces of Pataliputra, the modern Patna, the capital of their

empire. Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the Selecuids to the Court of

Chandragupta Maurya, reported that the palace compared in its magnificence with

the palace of Darius of Persepolis in Persia. The few ruins that survive appear

to confirm this. The Mauryans left traces of their rule in the

great royal palaces of Pataliputra, the modern Patna, the capital of their

empire. Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the Selecuids to the Court of

Chandragupta Maurya, reported that the palace compared in its magnificence with

the palace of Darius of Persepolis in Persia. The few ruins that survive appear

to confirm this.

The Arts of the Andhra Dynasty

The Andhra dynasty known to itself on

inscriptions by the name of Satavahana and by other names, enjoyed favorable

political circumstances, gave rise to the finest example of rock architecture,

along the northwestern and then on the east coast at Amaravati.

(image

source: India Ceylon Bhutan Nepal and the Maldives - By

The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples - volume 2. p. 313).

The Amravati School

The scenes depicted in Amaravati reliefs are

generally extremely complex and lively, with characters shown moving freely both

in groups and singly, and in a wide variety of stances. In the works at

Nagarjunakonda and Amaravati, the silpin, or Indian artist-craftsmen, achieve a

fusion of metaphysical and tactile reality, thereby attaining a unique balance

that gives Indian art a special place in the history of world art. The Indian

artist's unique contribution is to have created eternal values that are

immediately understood.

The Gandhara School

The school of Gandhara, which was more less

contemporary with the schools of Mathura and Amravati, developed and reached its

zenith in the northwest frontier zones, especially in Afghanistan and in the

area now known as Pakistan.

The Mathura School

Mathura stands on the Jumna river in western

Uttar Pradesh and close to one of India's oldest city. It lay on the main

trade routes from north India to the rest of Asia, and by the time of the Maurya

and Sunga dynasties (4th to 1st centuries B.C). was not only a leading

commercial and religious center and a place of pilgrimage for many different

sects, but also the focal point of a highly creative literary and artistic

school. The school of Mathura, with red sandstone sculptures, the material for

which was quarried from the Sikri caves outside the city, was contemporary with

the Gandhara school.

3. Gupta and Post-Gupta Arts

In the realm of sculpture and

painting Gupta art marks the highest reach of the Indian genius. Its influence

radiated over India and beyond. By the end of the Gupta period the whole region

of South East Asia had been deeply influenced by Indian thought and custom

especially in Indian religion. Its keynote is balance and freedom from

convention. It is thoroughly Indian in spirit and is marked by classic

restraint, a highly developed taste and deep aesthetic feeling. Its ideal was

the combination of beauty and virtue.

Notable panels such as the Gajendra moksha,

Vishnu reclining on Ananta, undoubtedly rank among the best specimens of Hindu

sculpture. Samudra Gupta issued no less than eight types of gold coinage of

great artistic value. Referring to the coin, which shows Samudra Gupta with the

Vina on the observe and Lakshmi on the reverse, Percy Brown says: ' the

excellent modeling of the king's figure, the skilful delineation of the

features, the careful attention to details and the general ornateness of the

design in the best specimens constitutes this type as the highest expression of

the Gupta numismatic art.

(source: Advanced

History of India - By Nilakanta Sastri and G. Srinivasachari

p.228-232).

The Gupta art is famous for Rupam or concept of

beauty. The Gupta artists applied themselves to the worship of beautiful form in

many ways. They worshipped art in order to awaken a new sense of spiritual joy

and nobility. There are many distinguishing features of the Gupta art. We find

both refinement and restraint. The Gupta artists relied more on elegance than on

volume. Their art showed simplicity of expression and spiritual purpose. Some of

the most beautiful images of Shiva belong to this period. They created the

Ardhanarishvara form of Shiva where the deity is represented as half male and

half female. The iron pillar near New Delhi is an outstanding example of Gupta

craftmanship. Its total height inclusive of the capital is 23 feet 8 inches. Its

entire weight is 6 tons. The pillar consists of a square abacus, the melon

shaped member and a capital. According to Percy Brown,

this pillar is a remarkable tribute to the genius and manipulative dexterity of

the Indian worker.

The cultural achievements of the Guptas evoked

praise from the historians, both foreign and Indian. According to L.

D. Barnett, "Gupta period is in the annals of classical India

almost what perclean age is in the history of Greece."

Vincent Smith

wrote: "The age of the great Gupta kings presented a more agreeable and

satisfactory picture than any other period in the history of Hindu India.

Literature, art and science flourished in a degree beyond ordinary and gradual

changes in religion were effected without persecution."

Sardar

Kavalam Madhava Panikkar

(1896-1963) observed:

"The two hundred years of the Gupta rule may be said to mark the climax of

Hindu imperial tradition."

Uma_Maheshwara

(image source: Indian and Indonesian Art - Ananda

Coomaraswamy).

***

The poet Kalidasa, was one of the "Nine Jewels" a group representing the

best minds of the kingdom, who were gathered together at the court of

Chandragupta II, in the 5th century A.D. The figurative art of the Gupta period

clearly shows that artists had a full knowledge of the best works produced and

the most advanced techniques developed in the past. There was intense commercial

and cultural intercourse between Asian mainland, and the influence of Gupta art

spread very widely, impressing its iconographical and stylistic tendencies on

many foreign artists. Chinese and Central Asian pilgrims came to India to visit

the shrines and to study in the best universities in the land.

This

was the Golden Age of Indian Art - of splendor and of the most flourishing

artistic resurgence to occur in India.

Dr. Ananda

Coomaraswamy, regarded Gupta art as the:

"flower of our established tradition, a polished and perfect medium, like

the Sanskrit language, for the establishment of thought and feeling. Its

character is self-possessed, urbane, at once exuberant and formal...Philosophy

and faith possess a common language in this art that is at once abstract and

sensuous, reserved and passionate."

(source: Ancient India -

By V. D. Mahajan p. 541).

A. L. Basham made

the following observation about the achievement of the Gupta period:

"This

was surely a period of high civilization in every sense, but especially in the

truest sense of the term - an age of equilibrium, when human relations reached a

degree of kindliness rare in the history of the world, and the best minds of

India expressed the fullness and goodness of life in imperishable art and

literature."

(source: Indian Heritage

and Culture - By P. Raghuanda Rao ISBN: 8120709292 p. 23).

Post Gupta Age

During the six centuries following the Gupta Age

(A.D 600-1200) the chief interest in the history of Indian art was centered

around the evolution of different types of temple architecture. A number of

temples were constructed. The grandest example of Orissan architecture is the

famous Sun temple of Konarak, a symphony in stone,

constructed during the reign of Narasimhadeva (1238-64). The

temple was conceived on a gigantic scale and was intended to be an architectural

replica of the chariot of the sun being whirled along through the heaven by

seven stately horses. Around the basement of the temple are twelve

giant wheels with beautiful carvings. At the main entrance are two caparisoned

steeds straining to drag the chariot through space. The whole building is

ornamented with exquisite sculptures presenting an alluring pageant of

sculptured magnificence. No wonder, Abul Fazl was

struck by the grandeur of the temple and wrote in his Ain-I-Akbari that “even

those whose judgment is critical and who are difficult to please stand amazed at

the sight.”

(source: Main Currents

in Indian Culture - By S. Natarajan p. 114).

A stunning instance of Orissan temple architecture, Konark’s

Sun temple has been aptly described by the famous Bengali poet Rabindranath

Tagore (1861-1941) poet, author, philosopher,

Nobel prize laureate

as:

"here

the language of stone surpasses the language of man", which means that the beauty of Konark is impossible to translate

into words.

Exquisitely carved wheel of a

chariot at the Sun Temple of Konark in Orissa.

Rabindranath

Tagore described Konark as 'here the language of stone surpasses the

language of man', which means the beauty of Konark is impossible to translate

into words.

For more

refer to chapter on Greater

India: Suvarnabhumi and Sacred

Angkor

***

Rock Temples and Monasteries

Hindu temples mostly dedicated to Shiva, were

carved in the rock at Ajanta and Ellora. Rock-cut

temple, 164 ft. deep, 109 ft. wide, 98 ft. high. Est. 200,000 tons of rock

excavated, reputedly using 1" chisels over a span of nearly 100 years.

Both as architecture and examples of

decoration they were more successful, in their simplicity, than were the

Buddhist temples, even though they followed the same general plan. Similar rock

cut shrines are also to be found on the island of Elephanta near Mumbai and

other places. In the temples dedicated to Shiva, the images do not usually crowd

one upon the other, as they often do in the Buddhist shrines. All is simpler and

more sober. The reliefs are placed at much greater intervals, displaying a more

mature spatial concept. The walls are decorated with

life size figures depicting mythological events, giving an overall effect of

monumentality and imposing power.

The

Kailasa Temple intended to be an earthly replica of Shiva’s splendor, the most

extensive and most sumptuous of the rock-cut shrines, worthy of being ranked

among the wonders of the world.

Philip

Meadows Taylor (1808 - 1876) an Anglo-Indian administrator

and novelist, was born in Liverpool, England.

He wrote on Ellora

: Philip

Meadows Taylor (1808 - 1876) an Anglo-Indian administrator

and novelist, was born in Liverpool, England.

He wrote on Ellora

:

“this carving on some of the

pillars, and of the lintels and architraves of the doors, is quite beyond

description. No chased work in silver or gold could possibly be finer. By what

tools this very hard, tough stone could have been wrought and polished as it is,

is not at all intelligible at the present day.”

(source: Story

of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage - By Will

Durant MJF Books. 1935. p. 601).

J. Griffiths

wrote: "There for centuries the wild ravine and the basaltic rocks were the

scene of an application of labor, skill, perseverance, and endurance that went

to the excavation of these painted palaces, standing to this day as monuments of

a boldness of conception and a defiance of difficulty as possible, we believe,

to the modern as to the ancient Indian character. The worth of the achievement

will be further evident from the fact that "much of the work has been

carried on with the help of artificial light, and no great stretch of

imagination is necessary to picture all that this involves in the Indian climate

and in situations where thorough ventilation is impossible."

Richard Lannoy has

written: “The Kailash temple at Ellora, a complete sunken Brahmanical temple

carved out in the late seventh and eighth centuries A.D is over 100 feet high,

the largest structure in India to survive from ancient times, larger than the

Parthenon. This representation of Shiva’s mountain home, Mount Kailash in the

Himalaya, took more than a century to carve, and three million cubic feet of

stone were removed before it was completed.

An

inscription records the exclamation of the last architect on looking at his

work: “Wonderful! O How could I ever have done it?”.

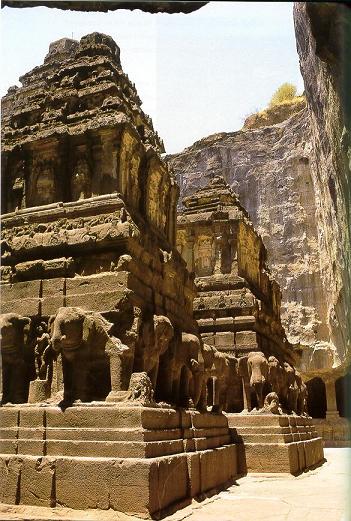

The Kailasa temple, Ellora

The largest structure in India to survive from ancient times, larger than the

Parthenon.

The temple of

Kailasa at Ellora is not only the most stupendous single work of art executed in

India but as an example of rock architecture it is unrivalled.

For more

refer to chapter on Greater

India: Suvarnabhumi and Sacred

Angkor

***

In Europe’s middle ages, the great cathedrals, including

the one of Chartres, rose from the ground upwards to the sky, supported not so

much by stone as by the powerful religious symbolism that drove the Christian

church. In India, the craftsmen did not build, but removed the earth and stone

to discover space in the service of a different religious symbolism, not one

identified with any religious monolith, but instead, one to which different

religious groups owed allegiance. Here Lannoy is more precise:

“A hollowed-out space in living rock is a totally different

environment from a building constructed of quarried stone. The human organism

responds in each case with a different kind of empathy. Buildings are fashioned

in sequence by a series of uniformly repeatable elements, segment by segment,

from a foundation upwards to the conjuction of walls and roof; the occupant

empathizes with a visible tension between gravity and soaring tensile strength.

Entering a great building is to experience an almost imperceptible tensing in

the skeletal muscles in response to constructional tension. Caves, on the other

hand, are scooped out by a downward plunge of the chisel from ceiling to floor

in the direction of gravity; the occupant empathizes with an invisible but

sensed resistance, an unrelenting presence in the rock enveloping him; sculpted

images and glowing pigments on the skin of the rock well forth from the deeps.

To enter an Indian cave sanctuary is to experience a relaxation of physical

tension in response to the implacable weight and density of solid rock.”

(source:

Decolonizing

History: Technology and Culture in India, China and the West

1492 to the Present Day - By Claude Alvares p.72-73).

Kailasa temple, Ellora

The greatest wonder of rock-cut in the world. One of the wonders of the world on

account of their huge dimensions and elaborate carvings.

The

grandest of them, the Hindu temple Kailasa (Shiva’s paradise) at Ellora, in

south-central

India

, ingeniously used the mountain itself to make the effigy of a divine mountain.

***

Rizwan

Salim writes about the beauty of Kailasa:

"Gaze

in wonder at the Kailas Mandir in the Ellora cave and remember that it is carved

out of a solid stone hill, an effort that (inscriptions say) took nearly 200

years. This is art as devotion. The temple

built by the Rashtrakuta kings (who also built the colossal sculpture in the

Elephanta caves off Mumbai harbour) gives proof of the ancient Hindus' religious

fervor. But the Kailas temple also indicated a will

power, a creative imagination, and an intellect eager to take on the greatest of

artistic challenges. The descendents of those who built the

magnificent temples of Bhojpur and Thanjavur, Konark and Kailas, invented

mathematics and urban surgery, created mind-body disciplines (yoga) of

astonishing power, and built mighty empires would almost certainly have attained

technological superiority over Europe."

(source: Need

for Cultural pride - Revival - By Rizwan Salim The Hindustan

Times 9/20/1998). For more on Kailasa, refer to World

Mysteries).

Daniel

J Boorstin

(1914 - 2004) American

historian, lawyer, professor, Librarian of Congress from 1975 to 1987,

prize-winning author of several books including The Discovers, The Creators and

The Seekers has observed:

"The

Hindu dynasties produced their many ornate versions of the primeval mountain –

dome, spire, hexagonal or octagonal tower. The surfaces and panels, the niches

and friezes of these stone monuments, bubble with images of plants, and

elephants, and of men and women in all postures. The

grandest of them, the Hindu temple Kailasa (Shiva’s paradise) at

Ellora, in south-central

India

, ingeniously used the mountain itself to make the

effigy of a divine mountain. A mountain-carved-out-of-mountain,

Kailasa was constructed by first cutting a trench into the mountain to isolate a

mass of rock 276 feet long, 154 feet wide, and 100 feet high. By working from

the top of the mass down, the rock cutters avoided the need for scaffolding. The

product of two hundred years’ labor was a worthy replica of Shiva’s

paradise,

Mount

Kailasa

in the

Himalayas

. Hindu architects and sculptors down to their latest efforts, as at Khajraho in

central

India

(c.1000), never gave up their rebuilding of

Mt.

Meru

, and spent their energy with ever greater profligacy in carving erotic images

of the reunion of man and his gods. The sikhara, or spires, which topped the

Hindu temple also meant mountain peak.

Perhaps

the most gigantic religious monument in the world is the temple complex of

Angkor Wat, built by King Suryavarman II as his sepulcher and the temple of his

divinity. The temple here, fantastically elaborated and multiplied, is a vast

filigreed steeped pyramid, a sculptured mountain.

"

(source:

The Discoverers - By Daniel J Boornstin p.

85 – 86).

K. De B. Codrington notes

the technical skills of the builders of the Kailash temple at Ellora:

"The monolithic Kailas temple of Ellora, with its

stupendous sculptures, is a marvel of engineering,

unsurpassed by any in the world…” The Kaislas (very closely

resembling in its outlines the Everest Peak, as Havell has demonstrated) has

been scooped out of a hill, and stands four-square in a court yard hewn from

solid rock, complete with gateways, nandi pavilion, staircases on either side,

porches and subsidiary shrines – formed by the chisel, and sculptured from top

to bottom without fault! "

(source: The

Legacy of India

- Edited by G. T. Garrett p. 94).

Robert

Payne (1911-) an American critic, and author of The

splendors of Asia : India, Thailand, Japan, in the Kailasa temple

at Ellora, for instance, he sees "nothing less

than the mountain of creation. It was here that Siva hammered out the

shapes of men and women of fables and mythologies of universes and

eternities." he writes. He is awed by the sweep of

imagination, the exuberance and tumult of creation itself, depicted in stone.

(source: spectrum:

tribuneindia.com).

About the truth and precision of the

work, which are no less admirable than its boldness and extent, J.

Griffiths has the following glowing testimony:

"During my long and careful

study of the caves I have not been able to detect a single instance where a

mistake has been made by cutting away too much stone; for if once a slip of this

kind occurred, it could only have been repaired by the insertion of a piece

which would have been a blemish."

(source: The

Paintings in the Buddhist Cave-Temple of Ajanta - By John Griffiths).

Percy Brown (1872-1955)

has

said:

"The temple of

Kailasa at Ellora is not only the most stupendous single work of art executed in

India, but as an example of rock architecture it is unrivalled.

Standing within its precincts and surrounded by its grey and hoary pavilions,

one seems to be looking through into another world, not a world of time and

space, but one of intense spiritual devotion expressed by such an amazing

artistic creation hewn out of the earth itself. Gradually one becomes conscious

of the remarkable imagination which conceived it, the unstinted labor which

enabled it to be materialized and finally the sculpture with which it is

adorned, this plastic decoration is its crowning glory, something more than a

record of artistic form, it is a great spiritual achievement, every portion

being a rich statement glowing with our meaning. The Kailasa is an illustration

of one of those rare occasions when men's minds, hearts, and hands work in

unison towards the consummation of a supreme ideal. It was under such conditions

of religious and cultural stability that this grand monolith representation of

Shiva's paradise was produced."

"The Kailasa Temple, it is safe to say, is

one of the most astonishing 'buildings' in the history of architecture. This

shrine was not constructed of stone on stone, it was in fact not constructed at